CW: This episode includes discussion of sexual themes, including incest and child sexual abuse. Listener discretion advised.

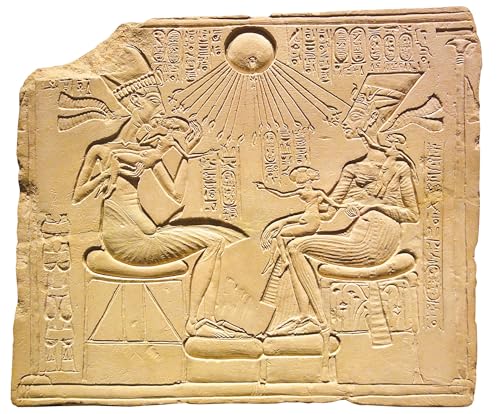

In this episode, Kara and Amber take on one of Amarna’s most famous images—the so-called “house altar” showing Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their three daughters beneath the Aten (Ägyptisches Museum/Neues Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Inv. no ÄM 14145). At a glance, this relief seems to show a sweet private scene of domesticity and familial affection, but taking the time to do some close-looking reveals how the scene might covey so much more. Kara unpacks how—to initiated elite eyes, at least—the piece encodes theology, court politics, sexual and reproductive power. What might Nefertiti’s unique blue crown signal about containment of solar power? Why are the girls’ bodies shown the way they are, like tiny women but with the heads of infants? And how might a palace loyalist use such an altar to telegraph succession hopes—and anxieties—without writing a word? It’s all here, encoded in the stone.

Along the way Kara and Amber also explore ancient Egyptian ideas of divine conception, the harem as a political machine, why Amarna “realism” isn’t exactly realism, but an idealized magical end goal, and how royal bodies carried the burden of sustaining royal legitimacy and succession.

Show notes

Object entry on Google Arts & Culture

For more on the commodification of women’s and girl’s bodies, see:

Episode #69 - Bodies and Power in the Ancient World

Cooney, Kathlyn M. 2025. Body power in the ancient world: patriarchal power and the commodification of women. In Thompson, Shane M. and Jessica Tomkins (eds), Understanding power in ancient Egypt and the Near East, volume I: Approaches, 104-135. Leiden; Boston: Brill. DOI: 10.1163/9789004712485_006.

For more on harems in ancient Egypt, see:

Episode #41 - Power and Politics in the Egyptian Harem

Cooney, Kathlyn M., Chloe Landis, and Turandot Shayegan 2023. The body of Egypt: how harem women connected a king with his elites. In Candelora, Danielle, Nadia Ben-Marzouk, and Kathlyn M. Cooney (eds),Ancient Egyptian society: challenging assumptions, exploring approaches, 336-348. London; New York: Routledge. DOI: 10.4324/9781003003403-31.

For the Amenhotep III conception scene discussed in the episode, see:

Krauss, Rolf. “Die Amarnazeitliche Familienstele Berlin 14145 Unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung von Maßordnung Und Komposition.” Jahrbuch Der Berliner Museen 33 (1991): 7–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/4125873.

Get full access to Ancient/Now at ancientnow.substack.com/subscribe

Dec 7 20251 hr and 4 mins

Dec 7 20251 hr and 4 mins 1 hr and 17 mins

1 hr and 17 mins Oct 24 20251 hr and 9 mins

Oct 24 20251 hr and 9 mins Oct 19 20251 hr and 6 mins

Oct 19 20251 hr and 6 mins Oct 18 20251 hr and 22 mins

Oct 18 20251 hr and 22 mins Sep 26 20251 hr and 54 mins

Sep 26 20251 hr and 54 mins 1 hr and 35 mins

1 hr and 35 mins 1 hr and 3 mins

1 hr and 3 mins